Among the many duties of the President of the United States is one that is found in Article II, Section 3 of the U.S. Constitution:

“He shall from time to time give to the Congress Information of the State of the Union, and recommend to their Consideration such Measures as he shall judge necessary and expedient….”

The Constitution does not specify in what manner the President is expected to furnish such “information” nor does it even suggest any certain season of the year — or any particular interval of time — that such “information” be provided. And, if conveyed verbally, the Constitution is silent as to from what physical location the President should perform this function.

Commonly referred to as the “State-of-the-Union” address, as President Franklin Delano Roosevelt dubbed it in 1934, President George Washington, the first man to occupy the high office of President of the United States, delivered the initial such regular, annual message before a joint session of Congress on January 8, 1790.

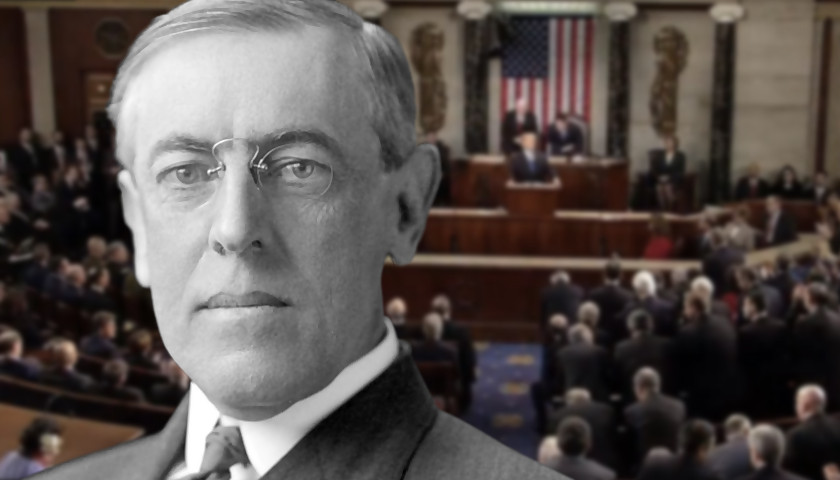

President Thomas Jefferson, our country’s third President, decided it better instead to send his remarks in written form to then be read to the membership by high-ranking Congressional employees. Jefferson’s idea held for more than a century until 1913, when President Woodrow Wilson re-established the practice of an in-person and spoken delivery before the two houses of Congress. And that tradition has stood ever since, with the exception of President Jimmy Carter’s January 1981 written message to Congress just prior to the inauguration of his successor, President Ronald Reagan.

With the ratification of the Constitution’s 20th Amendment, changing the commencement of new Presidential and Congressional terms from March 4th to January 3rd (for Congress) and January 20th (for the President) during odd-numbered years, the President has made the State-of-the-Union (or SOTU) address anywhere between January 3rd and February 12th and it was likewise during the Franklin Roosevelt administration that the tradition of speaking to Congress — and, by extension, to the entire nation — consistently from within the chamber of the United States House of Representatives began.

But what prompted President Woodrow Wilson in 1913 to restore the practice of a President personally delivering the SOTU remarks before Congress, something that had not been done since the administration of President John Adams — America’s second chief executive — concluded in 1801?

President Wilson was a man known for his energy, aggressiveness — and even combativeness. He was fond of noting that the office of President was a post “…in which a man must put on his war paint….” Wilson vigorously advocated an agenda described by historians as “progressive.” To a man of such a mindset, it seems to naturally follow that he would seek public approval for issues which he deemed to be important.

After all, his “plate” was quite full with tariff and income tax legislation; establishment of the Federal Reserve system; anti-trust measures; and, later in his second term, entry into World War I — to mention only a few.

A consummate politician, Wilson saw, with an in-person speech delivered before the two houses of Congress, a golden opportunity to persuade everyday Americans to climb aboard and join his demands for Congressional action upon his favored policy concepts. And what better way than the State-of-the-Union address to benefit from free publicity and a rapidly-transmitted and widely-received entreat?

President Wilson was not the first — and surely will not be the last — chief executive to astutely recognize the great message value of a nationally-broadcast and spoken SOTU address.

– – –

With his decade of work (1982-1992) to gain the 27th Amendment’s incorporation into the U.S. Constitution, Gregory Watson of Texas is an internationally-recognized authority on the process by which the federal Constitution is amended.

Thomas Woodrow Wilson was also a rabid racist. In order to win a three-way race to the White House in 1912, he had to trick disaffected black voters frustrated with the Republicans’ decision to abandon them to white voters to cross over and vote Democratic. Wilson did not have enough white voters in key northern states as a plurality of them supported either the Republican William Howard Taft or the Bull Moose Theodore Roosevelt. Wilson even feared he might need black votes in border states like Tennessee and Kentucky which, unlike many southeastern states, still had a sizable number of blacks who still voted. Although he turned out not to need the blacks he feared he would need in Tennessee, since the Bull Moosers and Republicans split their 49.9% vote in half, Wilson still won only a bare majority of Tennessee voters (ca. 51%)–very bad showing for a former Confederate state? He did far better in Mississippi, Louisiana, et al.

Once elected, he showed his “gratitude” to black by introducing and enforcing more more blatantly racist measures than his immediate predecessors. He purged many blacks from the Federal Civil Service and extended forced segregation. His wife wanted to go even further by attempting unsuccessfully to segregate Washington, D.C.’s public transit and public library systems. Those blacks like W.E.B. Dubois who had supported him in 1912 felt betrayed and returned to the G.O.P. until the New Deal some 25 years later would cause another black shift toward the Democrats.